Magical vibes at the U.S. Open; Neo-Nazi vibes on Tucker Carlson’s podcast; Edith Wharton in “a neighborhood of discreet hotels.”

I’m All Lost in …

The 3 things I’m obsessing about THIS week.

#47

1) It’s all true, I went to the U.S. Open on Thursday for the “evening session,” in this case: the Women’s Semifinals double header. The opening match starred my tennis hero, World No. 2 Aryna Sabalenka; in a promising sign, Sabalenka had destroyed the otherwise seemingly ascendant World No. 7 Qinwen Zheng in the quarterfinal on Tuesday night, 6-1, 6-4.

The minute I walked off the subway late Thursday afternoon (I took the F train from the Village to the 7 train toward Flushing), I was in a state: gliding along the boardwalk expanse onto the renowned tennis complex grounds (a mini-city, really), laughing out loud, amazed to have crossed the threshold into this bucket-list-item dreamland.

I arrived two-and-a-half hours early—at 4:30 for the 7:00 start—smiling without restraint, as I shambled through the buzzing crowd making my way from the chill-out park grounds and plazas with their abundant umbrella seating, past the regal fountains to the Grey Goose Vodka “Honey Deuce” drink stands (I certainly bought one of those); from the packed and wonderfully air-conditioned gift shops (I bought a shirt at the third shop I hit) to the walkway galleries memorializing historic players such as Molla Mallory, Althea Gibson, and Jimmy Connors.

At some point, I noticed the outdoor side courts that were clustered immediately west of majestic Arthur Ashe Stadium. My friend Gregory Samsa (he attends opening week every year) told me you can catch some background tournament action on these low-key courts. Fortuitously, I also remembered that a day earlier, one of the TV announcers noted that World No. 6 Jessica Pegula looked quite relaxed during her practice-court warmups in advance of her (big upset, it turned out) Wednesday match against World No. 1 Iga Swiatek.

At that, I decided to take a peek at the practice courts to see who I could find… imagining that… but knowing it probably wasn’t a possibility …. that there was no way I’d be so lucky… but…

First, I came across a Boys Wheel Chair match—both boys, in this instance, lacking the use of one ill-formed arm. It was a moving tableau. There weren’t many people watching, perhaps a few family members on the one row of silver benches. A young woman, was snapping away with a high-end camera.

I continued on to another court…and another… meandering through the labyrinth of fences, shallow stairwells, and white concrete landings, all the while feeling a bit sneaky. After a few minutes, I found myself walking alongside a pair of women, one in her late 20s, and another, my age, probably her mom, tentatively snooping around too. A bit disoriented in this maze of tennis courts, the three of us wound up in a skinny breezeway behind a court covered with a scrim. Suddenly, the young woman gasped: “It’s her!”

I knew who she meant and, all anticipation, I looked on as she pushed the netting aside for a view of the practice court at hand, leaning in as if she were a backstage Broadway tech in a head set, peering from behind the curtain. “Oh my god,” she said, “it is. It’s her.” She stepped aside and conspiratorially offered me a peek as well.

Aryna Sabalenka on Practice Court 3 at the U.S. Open complex, 9/5/24.

We realized there were some steps around the corner that led to a small set of bleachers. Our Nancy Drew excursion, it turned out, was completely legit: the practice session was for public viewing. We scrambled up and took our seats among a dozen or so other early birds to watch Sabalenka warm up on Practice Court 3.

She was hitting her famous sonic boom serve, and I got goosebumps in a moment of IRL recognition when I heard her racket crack down and swat the ball with such force that the echo took on a physical presence; it’s a weight you see, but don’t feel watching her on TV.

P.s. I didn’t even notice that Men’s World No. 1 Janik Sinner was hitting on the immediately adjacent court the whole time; I left after Sabalenka— who, I should note, looked quite relaxed—finished her warm up. By the way, Sabalenka’s average topspin forehand speed at the U.S. Open is 80 mph, faster than Sinner’s (78 mph), as well as faster than Men’s No. 2 Novak Djokovic’s (76) and men’s No. 3 Carlos Alacaraz’s (79).

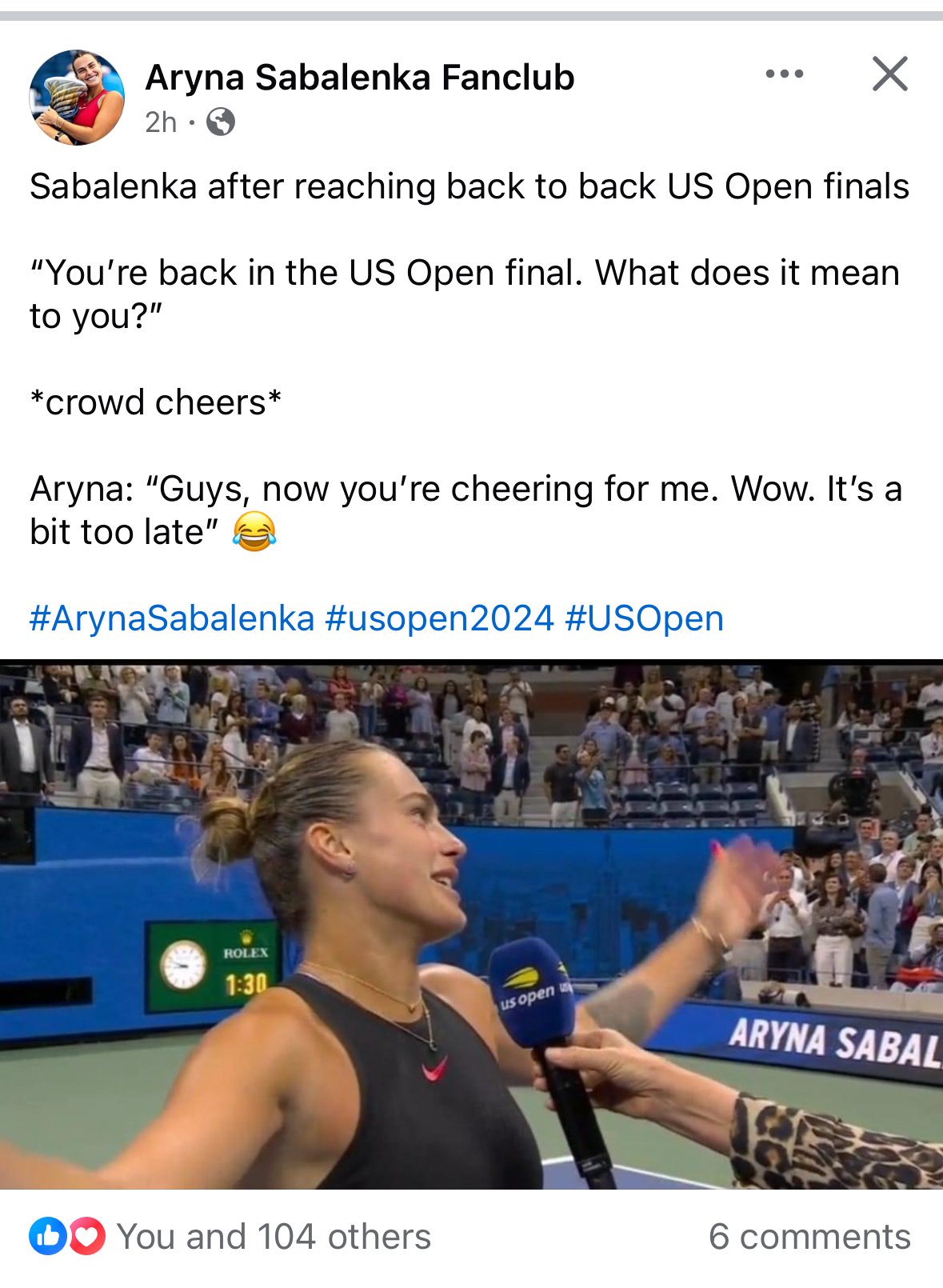

Two hours after watching Sabalenka warm up on Practice Court 3, I watched her play in the Semifinals at Arthur Ashe Stadium, dismissing surging billionaire’s kid, World No. 13, American Emma Navarro, in a riveting, blistering, and athletic match, 6-3, 7-6 (7-2). Luckily, the friendly people sitting next to me in our Section 326 nosebleed seats were playful about my Sabalenka partisanship even as they cheered the American through what ended up being a losing cause.

I hope whoever I’m sitting next to later this afternoon for the 4pm final between Sabalenka and American Pegula, is cool about it too.

2) Another Trump election means another season when neo-Nazi rhetoric goes mainstream via the felonious, traitorous ex-president’s MAGA ecosystem: Trump acolyte Tucker Carlson brought a Holocaust “revisionist” onto his popular “Tucker on X Podcast” this week.

Thank you NYT columnist Michelle Goldberg for editorializing about this noxious development and for connecting the dots to expose how antisemitism goes hand in hand with Trumpism and Trump’s media operatives.

Like your favorite poem, every line of Goldberg’s piece is worth pausing over and taking in full—from her keen explanation of how “Hitler curious” posturing poses as anti-establishment righteousness, to her take down of faux historians’ facile conclusions (equating Nazism with a liberal “state religion”), to her warnings about where “discarding … guardrails,” leads, namely, “Trump’s … authoritarian plans, including imprisoning masses of undocumented immigrants in vast detention camps.”

Goldberg offers a terminal diagnosis on the effects of swallowing Trump’s poison.

The weakening of the intellectual quarantine around Nazism — and the MAGA right’s fetish for ideas their enemies see as dangerous — makes it easier for influential conservatives to surrender to fascist impulses. When they do, they pay no penalty in political relevance, because there’s no conservative establishment capable of disciplining its ideologues.

3) I’m still digging into the Edith Wharton short story collection that I favorited late last month. I read a few more of her expertly crafted stories this week, including “The Journey,” about an existential cross country train trip, “The Rembrandt,” a slightly comedic, yet sad tale about a diminished elderly woman’s desperate version of the past (until the trick ending), and the observant “A Cold Cup of Water,” a parable about the human soul and, honestly, about the meaning of life; Wharton achieves this powerful bit of soothsaying as much though mood as through plot.

Wharton sets the vibe—a depressed resignation during end-of-the (19th)century Manhattan—with “the icy solitude of 5th Avenue,” the superficial manners on parquet ballroom dance floors, the ultimate futility of whiskey cafes, the “neighborhoods of cheap hotels” where third-floor rooms are “lit only by the upward gleam of electric globes in the street below,” and as Wharton opens the story, by the wet sidewalks, reflecting back at its denizens:

It had rained hard during the earlier part of the night, and the carriages waiting in triple line before the Gildermeres' door were still domed by shining umbrellas, while the electric lamps extending down the avenue blinked Narcissus-like at their watery images in the hollows of the sidewalk.

Wharton’s moody Manhattan gently cradles the story of a striver named Woburn, a well-intentioned young bank employee whose failure to make rank among the wealthy, fashionable set of one Miss Talcott, leads him into a sloppy, witless embezzlement scheme at work. Woburn’s downward spiral is reflected back to him through the tragic backstory of Ruby Glenn, a suicidal woman (she’s got a revolver) who he meets deep into night at the aforementioned hotel; both are in the throes of insomnia.

In fact, Wharton uses the tactic of mirroring throughout the story, particularly in this early haunting passage that ties mood and plot together with some uncomfortable foreshadowing:

The people on the sidewalks looked like strangers: he wondered where they were going and tried to picture the lives they led; but his own relation to life had been so suddenly reversed that he found it impossible to recover his mental perspective.

At one corner he saw a shabby man lurking in the shadow of the side street; as the hansom passed, a policeman ordered him to move on. Farther on, Woburn noticed a woman crouching on the door-step of a handsome house. She had drawn a shawl over her head and was sunk in the apathy of despair or drink. A well-dressed couple paused to look at her. The electric globe at the corner lit up their faces, and Woburn saw the lady, who was young and pretty, turn away with a little grimace, drawing her companion after her.

In the end, Woburn, who has achieved a new preternatural vantage of moral clarity, talks Ruby down and gives her the money she needs to return home. She, in turn, prompt’s Woburn’s own redemption.

Woburn's eyes were fixed on the window; he hardly seemed to hear her. At length he walked across the room and pulled up the shade. The electric lights were dissolving in the gray alembic of the dawn. A milk-cart rattled down the street and, like a witch returning late from the Sabbath, a stray cat whisked into an area. So rose the appointed day.

Woburn turned back, drawing from his pocket the roll of bills which he had thrust there with so different a purpose. He counted them out, and handed her fifteen dollars.

"That will pay for your board, including your breakfast this morning," he said. "We'll breakfast together presently if you like; and meanwhile suppose we sit down and watch the sunrise. I haven't seen it for years."

Later that morning, rather than acting on his own plan to flee New York aboard a steam ship, he returns to work with stoic resolve.

This door he also opened, entering a large room with wainscotted subdivisions, behind which appeared the stooping shoulders of a row of clerks.

As Woburn crossed the threshold a gray-haired man emerged from an inner office at the opposite end of the room.

At sight of Woburn he stopped short.

"Mr. Woburn!" he exclaimed; then he stepped nearer and added in a low tone: "I was requested to tell you when you came that the members of the firm are waiting; will you step into the private office?"